Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Mary McCaslin - Things We Said Today

A lot of Beatles fans out there won’t sit still for cover versions of the legendary band’s songs. To many of these listeners, the rock group “owns” every song they ever did, and any cover version will always be a pale imitation of their original recordings. I don’t blame the fans who feel that way. The Beatles are certainly a hard act to follow, and virtually every acetate they made is a miniature masterpiece.

But I believe that any truly great song is never “owned” by any one person (at least, not in the legal sense). To me, if a song can truly stand the test of time, it should be able to stand up to several different musical interpretations as well. When a cover version of a Beatles song is merely following the original recording’s instrumentation, then, I agree, such covers sound uninspired. But different arrangements of these songs can bring out other aspects to them that weren’t all that apparent in the originals.

Which brings me to my favorite Beatles cover: folk singer Mary McCaslin’s acoustic version of John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s “Things We Said Today,” which originally appeared on the Beatles albums A Hard Day’s Night in Britain and Something New in the U.S.

The Beatles’ version is given a full-band arrangement, with all four members chipping in on acoustic and electric instruments to surround the listener with a steady swirl of sound. But McCaslin strips the song down to two acoustic guitars and her solo voice, only occasionally double-tracked at strategic moments. McCaslin’s insistent picking of the guitar strings stresses the bass line and drives the song forward, while also emphasizing the tune’s wistful minor key. In place of the Beatles’ harmonizing vocals, McCaslin’s lone voice refocuses the lyrics as the thoughts of one individual, a quality of many Beatles songs that the group’s harmonies often clouded, and the unsynched double-tracked lyrics conjure the narrator’s haunting thoughts of her beloved.

Are you one of those who say a Beatles song can never be decently covered by another artist? Then listen to Mary McCaslin sing “Things We Said Today,” and see if you don’t change your mind. Somehow, I will know.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

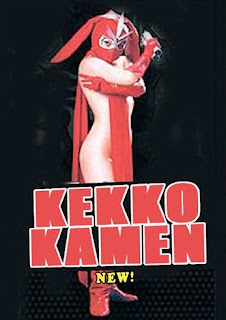

Nekkid Hero

Not long ago, I watched a live-action Japanese shot-on-video film, based on a manga (Japanese comic book), about Kekko Kamen, a superheroine who wears a mask, gloves, boots — and nothing else. It was one of the most ridiculous films I have ever seen. A laughable plot, contrived conflicts, unrealistic characters — all of these showed me the absurd lengths to which some filmmakers (if that’s not too generous a word for the creators of Kekko Kamen) will go to put some female skin on the screen.

In addition to being a manga and live-action video series, Kekko Kamen also exists as an anime series. The basic plots of all the episodes — manga, anime, and live-action video — are the same: a young, innocent schoolgirl at a sadistic boarding school run by a sinister and thuggish faculty is tormented by her teachers, often in a lewd and extravagant manner, only to be rescued in the nick of time by the almost-unclad Kekko Kamen, who uses her nude torso to distract the villains while her face-covering mask conceals her identity. Her alter ego is never revealed to us. Each episode begins and ends the same way, leading the serious-minded viewer to ask, “Why don’t the girls just leave the school?” Obviously, Kekko Kamen takes place on an exaggerated alternate Earth where such a question would never be asked and such a peculiarly costumed superhero wouldn’t be arrested for indecent exposure.

The reason why I mention this absurd exploitation movie is because Kekko Kamen makes farcical use of something that I think is a potentially serious concept: the nude hero. Today, when a nude body appears in story-telling media, that body will usually belong to a female, and her state of undress will signal her defenselessness in the face of the story’s malignant forces (think of the average slasher movie). This is understandable: conflict in stories (the engine of the narratives) is often expressed by violence, and the undressed body — to state the obvious — is not an optimum defense against brute force. So, the narrative idea of nudity as weakness is culturally overdetermined. And the naked human body — an organic locus of being which we all possess and which needs demystification — in a story will signal a potential victim or a work of eroticism, which is a rather limited way to perceive such an essential entity.

But this wasn’t always the case in representational media. Centuries ago, Greek, Renaissance, and Classical artworks expressed nakedness as power in statues and paintings of bare-bottomed Herculeses and Aphrodites seeming to draw strength and vigor from their absence of clothing. Granted, this is only a superficial view: volumes have been written about the nuances of nudity in works of art, how vintage depictions of the underdressed ancient gods were, for example, often a veiled form of eroticism. Still, this tradition in art marked one serious context that depicted nudity as something other than vulnerability and victimization. Could this tradition of nakedness as power be continued in non-erotic audio-visual media for mature audiences?

But depicting nude women also brings up another issue: the naked female as disempowered sexual object. While this approach is one very legitimate way of addressing this topic, it isn’t the only way. Much scholarship has been written about patriarchal artists and filmmakers using the image of the female nude to “control” feminine representation — and by extension, feminine behavior — in society. But even this academic view is premised on the idea that there is something worth controlling, that women are by their very nature something more than passive objects. Of course, one element that patriarchy usually seeks to control is women’s sexual attractiveness. And such patriarchal means of control can express itself in everything from the burka (keeping attractive women hidden) to the “girlie” magazine (channeling female attractiveness into a benign outlet so that it won’t channel itself into a more subversive one). Such efforts to “control” indicate that female attractiveness — including female nudity — carries its own disruptive power. True, this is a power that can easily be appropriated by patriarchy, but it is a power nevertheless. So, for all the talk of female nudity as disempowering “objectification,” a woman can still utilize her own nakedness as a source of strength — sexual, self-confident, and so on.

However, because nudity as a significant narrative element has been neglected by the more prestigious story-telling media (mainly out of a desire to reach their largest possible audiences, understandably), narrative emphasis on the bare human body has usually been relegated to eroticism or exploitation — hence, a cheaply made and silly toss-off like Kekko Kamen. But if a story were to use a knowingly naked hero or heroine in a serious and/or realsitic situation, what would such a use of nudity look like? For an idea, I would point to media that is, for the most part, disdained, disregarded, or little-seen.

A naked hero in a more solemn vein is Richard Corben’s science-fiction comic Den (also brought to the screen as a segment in the 1981 animated feature Heavy Metal). Den’s story takes place in an alternate, primitive world where fighting the bad guys and monsters sans apparel — as its muscle-bound eponymous hero does — is no big deal. Often grim and bloody but also whimsical, Corben’s comic serves as a serious rejoinder to Kekko Kamen’s laughably ludicrous stories. Still, like the Japanese manga (and the mythology-based paintings before it), Den signals to its readers that nakedness and heroism can only co-exist in a surrogate universe.

|

| ‘Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals’ (1977) |

What I like about the scene (when I can ignore the condescending portrayal of the “cannibals”) is that Emanuelle’s nudity becomes an agent of her personal power. The cannibals are so in awe of her naked body, and the confidence with which she wields it, that they surrender their prisoner to her. For all its obvious emphasis on the erotic, Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals is notable for its depiction of a woman who doffs her clothes and knowingly walks into a dangerous situation, and who escapes that situation precisely because she is naked to begin with. In one of those rare moments in the movies, a woman’s nudity is not a mark of vulnerability or victimization — but of strength. It’s difficult to think of a similar scene in all the rest of cinema.

However, a maker of more prestigious movies, Hungarian art-film director Miklós Jancsó, also uses nudity in an unconventional way. While in some of his films, Jancsó depicts the naked body as a sign of his characters’ humiliation and victimization by the antagonists, he depicts it in another way in many of his other movies. While Jancsó’s earlier films took place in naturalistic settings with traditional, story-driven narratives, his later ones became more allegorical, with characters representing larger themes rather than individuals with believable motives and behaviors. In these films, Jancsó utilizes nudity more for its symbolic value than as an indication of a character’s psychology.

One such film is Red Psalm (Még kér a nép, 1972). Notionally based on a failed Hungarian peasant uprising in the late 19th century, Jancsó’s “story” is more of a meditation on the issues surrounding how a proposed workers’ state would be philosophically different from the hierarchical capitalistic order with which it would have to struggle to come into being. The film is set entirely on an open field, but the place is more of a conceptual site for the conflicting agencies of Hungarian history to interact than it is an actual physical space. Consequently, Red Psalm doesn’t focus on any of the peasants or members of the ruling order individually; the people only represent the classes they belong to, with only a few of the characters differentiated from their groups. Made at a time when Hungary was a communist regime, this proselytizing film unambiguously takes the side of the proto-communist peasants, painting the ruling class and the army that supports it as less than fully human. In this context, Jancsó’s employment of nakedness serves to emphasize the peasants’ humanity, in contrast to the inhumanity of their uniformed and well-dressed opponents.

|

| Miklós Jancsó’s ‘Red Psalm’ (1972) |

However, precisely because the film is allegorical, the scene’s portrayal of powerful naked women walking undaunted into danger is just as fanciful and unbelievable as anything in Kekko Kamen (in a more naturalistic setting, the soldiers would likely attack the women). Red Psalm may be more serious and thoughtful than anything to do with the Japanese manga character, but the Hungarian film is no closer to portraying a practical and true-to-life imagining of naked heroism.

The physical body is a vital part of who we are as human beings, and its unclad state is a reminder of how we came into the world, as well as our being a part of it. For this reason, it seems limiting to relegate depictions of the naked body in our story-telling media primarily to erotic and exploitative cinema. The world of Classical art, for all its limitations, provided images of human nudity (even if primarily in the form of anthropomorphic deities) not solely in the realm of eroticism — and perhaps beyond it. I would like to see films, videos, and other contemporary story-telling media find a similar non-erotic (or not exclusively erotic) way of portraying the naked human body in a serious, verisimilitudinous context. One portrayal could be human nakedness as a sign of strength and power, rather than as a sign of titillation or vulnerability. And works like Kekko Kamen, Den, Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals, and Red Psalm indicate just how far off such an earnest and naturalistic depiction of naked heroism is.

Perhaps American society will first need to reverse the unclad human body’s social stigmatization. Perhaps its ghettoization into eroticism and exploitation is a reflection of society’s unacceptance of nudity outside very restricted contexts. But if we could get beyond this, we would still need to imagine what a more liberated use of the naked human body in film would look like. And how might it change cinema?

|

| Poster for the 2012 sequel ‘Kekko Kamen: Reborn’ |

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Film Noir, Part Three

Here is a post that I originally wrote on the Internet Movie Database:

Stylistically speaking, The Big Sleep (1946) is not the most exemplary film noir. The best noir films seethe with hard, stark shadows and heroes (or anti-heroes) feverishly unraveling under ominous circumstances. And The Big Sleep is missing this kind of visual and narrative delirium. The cinematography, compared to other film noirs, is relatively even-toned, and the lead character is too self-assured, and too reassuring to the viewer, to allow the story to spiral into uncertainty. In fact, Foster Hirsch, author of the book Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen, considers The Big Sleep to be the most overrated film noir.

However, The Big Sleep boasts something that no other film noir can: the ultimate film-noir actor — Humphrey Bogart — playing the ultimate film-noir character — quintessential hard-boiled private eye Philip Marlowe. And this distinction more than makes up for any stylistic shortcomings.

I wish that Bogart had done more films as Raymond Chandler’s creation. Wouldn’t it have been terrific if Warner Brothers had shortly afterwards adapted Chandler’s The High Window (a.k.a. The Brasher Doubloon) and The Lady in the Lake with Bogart playing Marlowe, instead of the adaptations that were ultimately made with other actors by other studios? In such a case, maybe Robert Montgomery’s noble experiment of a Hollywood movie seen almost entirely from a subjective camera — which his Lady in the Lake (1947) was — could have been based on a less canonical hard-boiled book. (But Dick Powell’s turn as Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet [1944] is so good that I wouldn’t want to erase it from the history books.)

Some might say that Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, also played by Bogart in The Maltese Falcon (1941), was the more definitive film-noir private eye and wish that Bogart had done more movies as that character instead. But Spade only appeared in that one novel and a few short stories, while Marlowe appeared in a series of novels by Chandler.

Since the actor’s death in 1957, Humphrey Bogart has become an icon, a true star of the cinema whose image and mannerisms are indelibly ingrained in our popular consciousness — so much so that the American Film Institute named him the greatest male screen legend of all time. Bogart has come to define the postwar Hollywood hard-boiled hero as much as John Wayne has come to define the western-movie hero. Even now, when a mystery movie depicts a streetwise sleuth, that character — however tangentially, however unconsciously, and often deliberately — evokes Bogart. And yet, he played fewer investigators in his varied career than his popular image would suggest.

I can’t help wondering what it would have been like if Bogart’s filmography did more to live up to that image of the definitive hard-boiled private eye. And I think that our popular conception of this kind of fictional figure owes more to the character of Philip Marlowe than it does to Sam Spade, whose name is usually invoked in summoning up this kind of detective. For these reasons, I think that a handful of big-budget films with this archetypal actor as this archetypal character would do better justice to the standings of both Bogart and Marlowe in our popular culture and our collective unconscious.

The trailer for ‘The Big Sleep’ (1946)

|

| Still from the trailer for ‘The Big Sleep’ (1946) |

However, The Big Sleep boasts something that no other film noir can: the ultimate film-noir actor — Humphrey Bogart — playing the ultimate film-noir character — quintessential hard-boiled private eye Philip Marlowe. And this distinction more than makes up for any stylistic shortcomings.

I wish that Bogart had done more films as Raymond Chandler’s creation. Wouldn’t it have been terrific if Warner Brothers had shortly afterwards adapted Chandler’s The High Window (a.k.a. The Brasher Doubloon) and The Lady in the Lake with Bogart playing Marlowe, instead of the adaptations that were ultimately made with other actors by other studios? In such a case, maybe Robert Montgomery’s noble experiment of a Hollywood movie seen almost entirely from a subjective camera — which his Lady in the Lake (1947) was — could have been based on a less canonical hard-boiled book. (But Dick Powell’s turn as Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet [1944] is so good that I wouldn’t want to erase it from the history books.)

Some might say that Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, also played by Bogart in The Maltese Falcon (1941), was the more definitive film-noir private eye and wish that Bogart had done more movies as that character instead. But Spade only appeared in that one novel and a few short stories, while Marlowe appeared in a series of novels by Chandler.

Since the actor’s death in 1957, Humphrey Bogart has become an icon, a true star of the cinema whose image and mannerisms are indelibly ingrained in our popular consciousness — so much so that the American Film Institute named him the greatest male screen legend of all time. Bogart has come to define the postwar Hollywood hard-boiled hero as much as John Wayne has come to define the western-movie hero. Even now, when a mystery movie depicts a streetwise sleuth, that character — however tangentially, however unconsciously, and often deliberately — evokes Bogart. And yet, he played fewer investigators in his varied career than his popular image would suggest.

I can’t help wondering what it would have been like if Bogart’s filmography did more to live up to that image of the definitive hard-boiled private eye. And I think that our popular conception of this kind of fictional figure owes more to the character of Philip Marlowe than it does to Sam Spade, whose name is usually invoked in summoning up this kind of detective. For these reasons, I think that a handful of big-budget films with this archetypal actor as this archetypal character would do better justice to the standings of both Bogart and Marlowe in our popular culture and our collective unconscious.

The trailer for ‘The Big Sleep’ (1946)

Labels:

cinema,

film,

film noir,

Hollywood,

Humphrey Bogart

Saturday, August 13, 2011

I’m a ‘Movie Fan Fare’ Guest Blogger

The website Movie Fan Fare has posted a review of mine, a condensed version of my blog post about Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure. They posted it Monday, and it’s received 39 comments so far. Not too shabby.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

My 10 Favorite Action Films

I became a movie buff by watching the great art films, character dramas, and romantic comedies of decades past. Those are the kinds of movies that I truly love. When I was becoming aware of the cinema, “action movies” meant Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson or some other monosyllabic marksman blowing away or beating up some two-dimensional bad guy in stories with no emotional depth or narrative complexity. Only the balletic martial-arts moves of Bruce Lee and the other emerging kung-fu stars of Hong Kong provided an alternative, where action did not mean cruelty, and strength did not mean sheer brute force. But as much as I relished their artful acrobatics, the Hong Kong films themselves seemed crudely made and thematically underdeveloped.

Recent Discovery: LEGEND OF THE BLACK SCORPION (a.k.a. The Banquet)

Directed by Feng Xiaogang (China/Hong Kong, 2006)

A retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet transposed to tenth-century China, but with a twist — the usurping emperor’s queen (Crouching Tiger’s Zhang Ziyi) is also the prince’s beloved. In other words, imagine Hamlet if Claudius took over the Danish throne and married Ophelia instead of Gertrude. The complexity of the plot and characters matches the sumptuousness of the art direction. The fictional figures of the story are as intricate as those in any drama (which the film aspires to be, hence its less action-oriented alternate title), but the heightened conventions of the kung-fu film — gravity-defying combatants, superhuman swordplay — suffuse the narrative as well. A resplendent combination of high drama and populist entertainment uncommon in occidental cinema.

Only more recently, in my view, have filmmakers coupled clever and intelligent story lines with action scenes whose cinematic engagement packs the same visceral punch as the physical conflicts they depict. So, I have become an aficionado of action movies fairly late in the game. And by “action movie,” I mean those stories of derring-do, those somewhat pulpy parables where men and women of great physical skill draw upon their best resources to defeat an impending evil. I do not pretend to be a connoisseur — after all, I'm sure that I have seen relatively few Asian or occidental action movies compared to those who seek them out and live on a steady diet of rifles and roundhouse kicks. But of those that I have seen, these are my favorites...

Directed by Akira Kurosawa (Japan, 1954)

Really more than a mere “action movie,” this tale of seven masterless rônin — who defy the class distinctions of feudal Japan to rescue a peasant village — brims over with keen human insight. The story sensitively explores how the adventure disrupts the lives of both the warriors and the villagers, all of whom are drawn as fully dimensional characters. But the film’s fervid action scenes hold the sprawling story together. Epic in the best sense of the word.

Directed by Akira Kurosawa (Japan, 1961)

Another major work by that Shakespeare of the chambara (and of virtually every other kind of film he directed), Akira Kurosawa. A wandering rônin comes to a small town ruled by two feuding crime families, and he sets them against each other. The story is cunningly clever and complex, matched by the swift precision of the swordfight scenes. As the “bodyguard” of the title, Toshirô Mifune has never been more charismatic. Later remade as the spaghetti western A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and the gangster picture Last Man Standing (1996).

Directed by George Miller (Australia/USA, 1981)

Running at a lean 91 minutes, this parable of post-apocalyptic road rage is a no-nonsense story of easily identifiable good guys and bad guys. In a world after nuclear holocaust, an outsider tries to save a village preyed on by marauders. The plot isn’t especially complex, and the characters are little more than action-movie archetypes. But the tautness of the story and the adrenaline-pumping impact of the car-chase scenes thrive on their own. The movie that made an international star of Mel Gibson.

Directed by Tsui Hark (Hong Kong, 1986)

I may be a little prejudiced because this was the first of the “New Wave” Hong Kong action films that I saw, but I still think it’s the best of the bunch. The story is a bit comic-bookish — a ragtag team of republican revolutionaries in post-imperial China struggles against corrupt warlords and an evil gang boss — but it also touches on some surprisingly complex subjects: political commitment, family loyalty, female empowerment, and even transvestism. Director Tsui skillfully balances electrifying action with genuinely hilarious humor, all of which leads to a rousing climax. Pulpy, playful, and unpretentiously profound all at the same time.

Directed by Ang Lee (Taiwan/ China/USA, 2000)

Okay, so everybody already knows about this critically lauded and surprisingly popular “martial-arthouse” movie. But it has also garnered more than its fair share of hostile comments. Many have argued that it’s not particularly original and that its action scenes pale in comparison to the Hong Kong wuxia movies of the 1960s and ’70s. But Crouching Tiger can boast much better developed characters, a carefully cultivated story, and effective performances by the cast. In addition to having visceral, vibrantly staged fight scenes, this film has soul.

Directed by Paul Verhoeven (USA, 1987)

The notorious Dutch director’s Hollywood debut not only possesses some gut-wrenching action, a strong story line, and weighty themes of identity and individuality, but the movie is also a very witty political satire. A policeman is brutally killed in the line of duty but resurrected as a crime-fighting android. The man-machine is supposed to have no personality, but the policeman’s memory comes back and discovers high crimes committed by the company that revived him. In addition to its heart-pounding shoot-’em-up scenes, the movie is an incisive meditation on the loss of humanity in a corporate culture. To quote one of the film's bad guys after he has just demolished a building with a munitions-grade firearm, “I like it!”

Directed by Ching Siu-Tung (Hong Kong, 1989)

An underappreciated gem from Hong Kong, this swordplay adventure tells a genuinely touching story of a guardsman to China's first emperor who awakens in the 20th century and believes that he’s found his lost love. The mythic narrative and Ching’s deft handling of the martial mayhem would automatically make this movie worth watching, but the film’s real standout is its off-kilter casting. Not only is the dual-role female lead played by dramatic diva Gong Li, but the action hero is played by her then-significant other and art-film director Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern, House of Flying Daggers). Just imagine Ingmar Bergman playing John Wayne, and you’ll get an idea of how bizarre the casting is. Still, Zhang makes an effective leading man, and the stars’ off-screen auras never interfere with the gripping story.

Directed by Stanley Tong (Hong Kong, 1993)

Crouching Tiger’s Michelle Yeoh reprises her comeback role as Inspector Yang, the by-the-book Chinese policewoman she created in Tong’s Police Story III: Supercop, opposite Jackie Chan. In this superb spin-off, Inspector Yang is summoned to Hong Kong to catch a gang of master thieves, only to learn that the gang is headed by her fiancé (Iron Monkey’s Yu Rong-Guang). Yang’s struggle between her feelings and her duties gives the air-tight story a surprising and effective emotional depth. And the action scenes pack an equally powerful punch. The dubbed and edited version available on video in the U.S. under the title Supercop 2 does no great damage to the original and actually better helps to convey the characters’ emotions to an English-speaking audience.

Directed by Andrzej Bartkowiak (USA, 2000)

Wherefore art thou Romeo? Valid complaints that Jet Li’s “Romeo” ends the movie as more of a platonic pal to his Juliet — and the dehumanizing stereotype of an Asian parent having his own child murdered — have unfortunately overshadowed this film’s strengths. The plot is plausible, intriguing, and easy to follow. The action scenes wallop the eye. And the characters display more emotional depth than the typical pulp-action archetypes. Jet Li’s first Hollywood starring vehicle remains a hard act to follow.

Directed by Ching Siu-Tung and Raymond Lee (Hong Kong, 1993)

No movie list is complete without something from the category of weird and whacked out. In this spin-off to 1992’s supernatural swashbuckler Swordsman II, the very feminine Brigitte Lin of Peking Opera Blues goes tranny again by reprising her role as Asia the Invincible, a man who gained magical powers by having himself castrated. Gender is bent past the breaking point as Lin’s ruthless and destructive sorcerer moves easily between male and female identities. The uncertainty of Asia’s sexual identity suggests a similar uncertainty of Hong Kong’s national identity on the eve of its hand-over to China. And this gives the explosive mayhem at the movie’s end an insurgent edge: the cataclysmic climax implies both national anxiety in the face of totalitarian takeover and a fiery display of defiance. Deliciously delirious — and a bit ludicrous in places — but with an urgent undertone of political rebellion.

Recent Discovery: LEGEND OF THE BLACK SCORPION (a.k.a. The Banquet)

Directed by Feng Xiaogang (China/Hong Kong, 2006)

A retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet transposed to tenth-century China, but with a twist — the usurping emperor’s queen (Crouching Tiger’s Zhang Ziyi) is also the prince’s beloved. In other words, imagine Hamlet if Claudius took over the Danish throne and married Ophelia instead of Gertrude. The complexity of the plot and characters matches the sumptuousness of the art direction. The fictional figures of the story are as intricate as those in any drama (which the film aspires to be, hence its less action-oriented alternate title), but the heightened conventions of the kung-fu film — gravity-defying combatants, superhuman swordplay — suffuse the narrative as well. A resplendent combination of high drama and populist entertainment uncommon in occidental cinema.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)