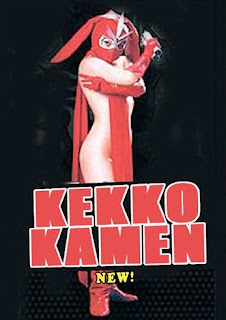

Not long ago, I watched a live-action Japanese shot-on-video film, based on a manga (Japanese comic book), about Kekko Kamen, a superheroine who wears a mask, gloves, boots — and nothing else. It was one of the most ridiculous films I have ever seen. A laughable plot, contrived conflicts, unrealistic characters — all of these showed me the absurd lengths to which some filmmakers (if that’s not too generous a word for the creators of Kekko Kamen) will go to put some female skin on the screen.

In addition to being a manga and live-action video series, Kekko Kamen also exists as an anime series. The basic plots of all the episodes — manga, anime, and live-action video — are the same: a young, innocent schoolgirl at a sadistic boarding school run by a sinister and thuggish faculty is tormented by her teachers, often in a lewd and extravagant manner, only to be rescued in the nick of time by the almost-unclad Kekko Kamen, who uses her nude torso to distract the villains while her face-covering mask conceals her identity. Her alter ego is never revealed to us. Each episode begins and ends the same way, leading the serious-minded viewer to ask, “Why don’t the girls just leave the school?” Obviously, Kekko Kamen takes place on an exaggerated alternate Earth where such a question would never be asked and such a peculiarly costumed superhero wouldn’t be arrested for indecent exposure.

The reason why I mention this absurd exploitation movie is because Kekko Kamen makes farcical use of something that I think is a potentially serious concept: the nude hero. Today, when a nude body appears in story-telling media, that body will usually belong to a female, and her state of undress will signal her defenselessness in the face of the story’s malignant forces (think of the average slasher movie). This is understandable: conflict in stories (the engine of the narratives) is often expressed by violence, and the undressed body — to state the obvious — is not an optimum defense against brute force. So, the narrative idea of nudity as weakness is culturally overdetermined. And the naked human body — an organic locus of being which we all possess and which needs demystification — in a story will signal a potential victim or a work of eroticism, which is a rather limited way to perceive such an essential entity.

But this wasn’t always the case in representational media. Centuries ago, Greek, Renaissance, and Classical artworks expressed nakedness as power in statues and paintings of bare-bottomed Herculeses and Aphrodites seeming to draw strength and vigor from their absence of clothing. Granted, this is only a superficial view: volumes have been written about the nuances of nudity in works of art, how vintage depictions of the underdressed ancient gods were, for example, often a veiled form of eroticism. Still, this tradition in art marked one serious context that depicted nudity as something other than vulnerability and victimization. Could this tradition of nakedness as power be continued in non-erotic audio-visual media for mature audiences?

But depicting nude women also brings up another issue: the naked female as disempowered sexual object. While this approach is one very legitimate way of addressing this topic, it isn’t the only way. Much scholarship has been written about patriarchal artists and filmmakers using the image of the female nude to “control” feminine representation — and by extension, feminine behavior — in society. But even this academic view is premised on the idea that there is something worth controlling, that women are by their very nature something more than passive objects. Of course, one element that patriarchy usually seeks to control is women’s sexual attractiveness. And such patriarchal means of control can express itself in everything from the burka (keeping attractive women hidden) to the “girlie” magazine (channeling female attractiveness into a benign outlet so that it won’t channel itself into a more subversive one). Such efforts to “control” indicate that female attractiveness — including female nudity — carries its own disruptive power. True, this is a power that can easily be appropriated by patriarchy, but it is a power nevertheless. So, for all the talk of female nudity as disempowering “objectification,” a woman can still utilize her own nakedness as a source of strength — sexual, self-confident, and so on.

However, because nudity as a significant narrative element has been neglected by the more prestigious story-telling media (mainly out of a desire to reach their largest possible audiences, understandably), narrative emphasis on the bare human body has usually been relegated to eroticism or exploitation — hence, a cheaply made and silly toss-off like Kekko Kamen. But if a story were to use a knowingly naked hero or heroine in a serious and/or realsitic situation, what would such a use of nudity look like? For an idea, I would point to media that is, for the most part, disdained, disregarded, or little-seen.

A naked hero in a more solemn vein is Richard Corben’s science-fiction comic Den (also brought to the screen as a segment in the 1981 animated feature Heavy Metal). Den’s story takes place in an alternate, primitive world where fighting the bad guys and monsters sans apparel — as its muscle-bound eponymous hero does — is no big deal. Often grim and bloody but also whimsical, Corben’s comic serves as a serious rejoinder to Kekko Kamen’s laughably ludicrous stories. Still, like the Japanese manga (and the mythology-based paintings before it), Den signals to its readers that nakedness and heroism can only co-exist in a surrogate universe.

|

| ‘Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals’ (1977) |

What I like about the scene (when I can ignore the condescending portrayal of the “cannibals”) is that Emanuelle’s nudity becomes an agent of her personal power. The cannibals are so in awe of her naked body, and the confidence with which she wields it, that they surrender their prisoner to her. For all its obvious emphasis on the erotic, Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals is notable for its depiction of a woman who doffs her clothes and knowingly walks into a dangerous situation, and who escapes that situation precisely because she is naked to begin with. In one of those rare moments in the movies, a woman’s nudity is not a mark of vulnerability or victimization — but of strength. It’s difficult to think of a similar scene in all the rest of cinema.

However, a maker of more prestigious movies, Hungarian art-film director Miklós Jancsó, also uses nudity in an unconventional way. While in some of his films, Jancsó depicts the naked body as a sign of his characters’ humiliation and victimization by the antagonists, he depicts it in another way in many of his other movies. While Jancsó’s earlier films took place in naturalistic settings with traditional, story-driven narratives, his later ones became more allegorical, with characters representing larger themes rather than individuals with believable motives and behaviors. In these films, Jancsó utilizes nudity more for its symbolic value than as an indication of a character’s psychology.

One such film is Red Psalm (Még kér a nép, 1972). Notionally based on a failed Hungarian peasant uprising in the late 19th century, Jancsó’s “story” is more of a meditation on the issues surrounding how a proposed workers’ state would be philosophically different from the hierarchical capitalistic order with which it would have to struggle to come into being. The film is set entirely on an open field, but the place is more of a conceptual site for the conflicting agencies of Hungarian history to interact than it is an actual physical space. Consequently, Red Psalm doesn’t focus on any of the peasants or members of the ruling order individually; the people only represent the classes they belong to, with only a few of the characters differentiated from their groups. Made at a time when Hungary was a communist regime, this proselytizing film unambiguously takes the side of the proto-communist peasants, painting the ruling class and the army that supports it as less than fully human. In this context, Jancsó’s employment of nakedness serves to emphasize the peasants’ humanity, in contrast to the inhumanity of their uniformed and well-dressed opponents.

|

| Miklós Jancsó’s ‘Red Psalm’ (1972) |

However, precisely because the film is allegorical, the scene’s portrayal of powerful naked women walking undaunted into danger is just as fanciful and unbelievable as anything in Kekko Kamen (in a more naturalistic setting, the soldiers would likely attack the women). Red Psalm may be more serious and thoughtful than anything to do with the Japanese manga character, but the Hungarian film is no closer to portraying a practical and true-to-life imagining of naked heroism.

The physical body is a vital part of who we are as human beings, and its unclad state is a reminder of how we came into the world, as well as our being a part of it. For this reason, it seems limiting to relegate depictions of the naked body in our story-telling media primarily to erotic and exploitative cinema. The world of Classical art, for all its limitations, provided images of human nudity (even if primarily in the form of anthropomorphic deities) not solely in the realm of eroticism — and perhaps beyond it. I would like to see films, videos, and other contemporary story-telling media find a similar non-erotic (or not exclusively erotic) way of portraying the naked human body in a serious, verisimilitudinous context. One portrayal could be human nakedness as a sign of strength and power, rather than as a sign of titillation or vulnerability. And works like Kekko Kamen, Den, Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals, and Red Psalm indicate just how far off such an earnest and naturalistic depiction of naked heroism is.

Perhaps American society will first need to reverse the unclad human body’s social stigmatization. Perhaps its ghettoization into eroticism and exploitation is a reflection of society’s unacceptance of nudity outside very restricted contexts. But if we could get beyond this, we would still need to imagine what a more liberated use of the naked human body in film would look like. And how might it change cinema?

|

| Poster for the 2012 sequel ‘Kekko Kamen: Reborn’ |

No comments:

Post a Comment