For as long as I can remember, a light touch to my head or face, or maybe even a certain sound of voice, would give me a quick tingling sensation in my head. The tingling was very pleasurable, like swarming beads of euphoria dancing around in my cranium, and sometimes around my face, with joyous abandon. This sensation was very infrequent — it would only occur a handful of times a year — and very fleeting. I could only enjoy the ecstasy of the sensation for a few seconds before it was gone and I had to get back to whatever I was dealing with before it hit. Because the sensation was so rare and so ephemeral, I barely thought about it at all, despite the immense pleasure it gave me. And it never occurred to me to give the sensation a name.

That all changed

last year. It changed while I was

surfing the Web. I don’t remember

how or why I came across what I did.

Given the importance of the discovery to me, you’d think that I would

remember my path to it in great detail.

But no such luck. What was

my discovery?

Last

year, while exploring the Internet, I stumbled upon the phrase Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, or ASMR for short. And

I learned that it described that tingling sensation that I had

experienced all my life. My

electronic travels led me in short order to a series of YouTube videos by

various users, videos whose purpose was to trigger the euphoric feeling in their

viewers, usually by the video-maker whispering to the camera. So, this pleasant tingling sensation, I realized, was something that others felt as well, and it was something that could be induced. My mind was blown like Louis Armstrong’s trumpet.

I’m

trying to remember more about my reaction to this discovery. But I recall so little about that day

that it might as well have been 100 years ago. Maybe I don’t remember it very well because I was so

overwhelmed: not only did other people

feel the sensation, but it was important enough to have a name. The only other thing that I can remember

about that day is my bewilderment about why it had never occurred to me to try

and trigger the rapturous tingling in myself.

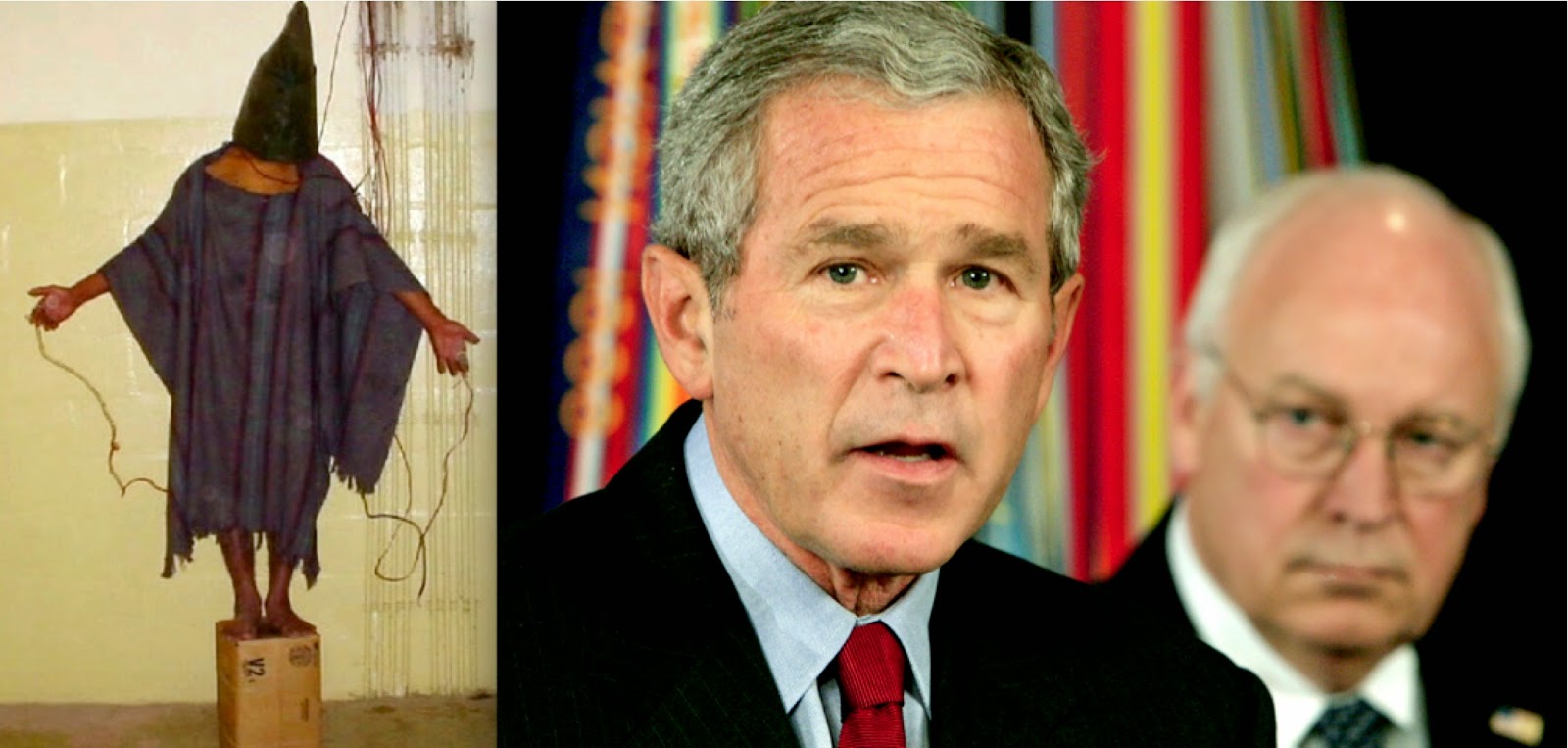

YouTube’s most popular “ASMRtist,” GentleWhispering, who has over 300,000 subscribers

I checked

out some of the ASMR videos, most made by whispering female YouTubers, often role-playing some moment of intimacy or tender attention, such as a haircut. As I watched these videos, wave after

wave of intense tingling swirled around the inside of my skull. Although each wave lasted only ten seconds at most, and usually less, it would quickly be followed by another. I felt as though I had discovered some

high-inducing opiate.

And now,

I need to make the disclaimer that everyone who experiences ASMR is quick to

note: Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response is not sexual. Despite some of the ASMR video-makers’ affectations of

intimacy, this is not a sensation that I experience below the belt. While others (I have since learned)

report of feeling it throughout their bodies, my own experience is usually

confined to my head and never goes lower than my shoulders. I wouldn’t be surprised if the brain’s

activity during ASMR draws upon the same pleasure centers that are activated by

sex, but the sensation itself is not erotic.

While “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response” is a scientific-sounding name, nothing is known about it scientifically.

Scientists have not found a way to measure ASMR. Some studies have begun that examine the ASMR experience

with an MRI, but last I heard, those studies were still in the preliminary

stages and far from complete. The

phrase “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response” was coined by one Jenn Allen. She felt that such a phrase was needed

because those who would talk about the sensation, lacking a better name, would

liken it to a sexual experience and call it things like “brain orgasm.” Allen wanted to distinguish the

sensation from sex, so she invented a name without carnal connotations.

An ASMR role-play video by the YouTube user VeniVidiVulpes

You might

wonder why it’s taken me so long to post about ASMR. Well, when watching my first batch of tingle-triggering

YouTube videos, the intensity of the sensation began wearing off after about

half an hour. I returned to

watching videos the next day, but the tingling, when I felt it at all, was

barely noticeable. I had to stop

watching the videos for several days before the intensity of the tingling would

return. Because of this, I took a

hiatus from ASMR videos for several months. Only recently have I started watching them again, and only

recently did I truly realize just how important this euphoric experience is to

me.

I have

also joined an ASMR community on Facebook. From what I have read there and elsewhere on the Internet, I

get the idea that others who experience ASMR find it very easy to trigger in

themselves. If this is true, I

seem to be someone in whom the sensation is difficult to induce and who, unfortunately, becomes inured to it relatively quickly. Maybe I can find a way to change

that. At the moment, the YouTuber

who can best induce ASMR in me is the user GentleWhispering (a.k.a. Maria), but other

video-makers who specialize in triggering ASMR — or

“ASMRtists,” as they call themselves — abound on YouTube. For those who don’t experience ASMR,

these videos will appear boring, perhaps not unlike the way pornography would

be boring to a viewer without a sex drive.

Since I

have trouble remembering how I came across the phrase Autonomous Sensory

Meridian Response, I’m embedding a video of a This American Life radio broadcast, in which the

correspondent, who also experiences ASMR, recounts her discovery of the phrase

and the community that has grown up around it. I’ll also link to a couple other articles on the Web.

.jpg)